Lessons that incorporate experimentation and student choice can transform the learning experience for students. In these lessons students grapple with complex tasks and set their own goals, and in doing so, develop important transferable skills like time management and how to work well with a team, as well as develop problem-solving strategies. They also learn about the importance of self-reflection, grit, and continued exploration based on their findings.

Erin Magee, a 5th Grade Science Teacher at Charles E. Smith School in Rockville, Maryland wanted to focus on using experimentation coupled with goal setting and reflection in her classes. With the help of her BetterLesson Instructional Coach, Chris Dewald, with whom she met virtually every other week throughout the school year, Erin tried strategies and mapped a plan for how to incorporate goal setting and reflection into her teaching approach during experiments. In the interview below, Erin and Chris respond to our questions about how Erin successfully integrated goal setting and reflection into her classroom.

Q. How do goals support student personal growth in the classroom?

Erin Magee: When my students had an individualized goal, I found that they were more engaged and motivated than before. Giving students the autonomy to think about what they want to learn or experiment with, and then allowing them to figure out what they need to do to get there, is so empowering for students at any age.

Chris DeWald: While working with Erin, I noticed that although her students used Progress and Mastery Tracking to demonstrate their growth, they often had trouble honoring their own growth. Also, we found that using mastery trackers was more successful in math than in science because math progresses in a more linear fashion, and science is more focused on non-linear topics. However, when students developed personalized goals and reflected on them with Erin, they were better able to identify and celebrate their successes. This was successful in both math and science, and helped to overcome the challenges presented by the less linear science content.

Q. How do we give students ownership by having them set their own personal goals?

EM: I found that with my students, the goals need to be individualized. Generic goals aren’t motivating for students because they lack a relevant context for them. It is important to establish a baseline understanding of how to imagine a goal and set steps to reach that goal. Once students have practiced as a group, they are better prepared to create a relevant goal using that information. In science class, it often feels like we need to start experimenting and learning so that we can establish a baseline set of standards for goal setting. Once we have that, students can decide where they want to go, which goal they wish to set and achieve, and take ownership of their process in getting there. Including time for students to reflect on how they are accomplishing their goal allows them to become more experienced in setting personal goals. Providing students with ideas and feedback about how to achieve their personal goals in a manageable fashion is another important role teachers can play.

CD: Supporting students to set meaningful and measurable goals is an important step in building a student-centered classroom. Some strategies that I would suggest trying in order to support students to develop their own goals are SMART Goal Setting and Weekly Goal Setting and Reflection. One thing that Erin found especially helpful was to include procedural items within the goals. For example, students could set goals about collecting and returning their materials when doing a lab, or about the ways in which they collected and analyzed data. Expanding the goal topic beyond just assessment scores or data was more relevant and actionable for the students.

Q. What are the ground rules that we need to have in order for goal setting to be successful?

EM: I’ve found that norming around adhering to our timelines and being done when experimentation time is done is important. I try to make sure my students are aware of time constraints in order to help them create smaller, more specific daily goals that eventually lead to the completion of a much larger goal.

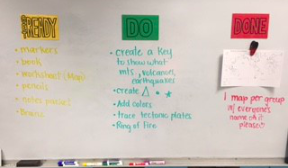

Also being prepared and having the appropriate materials for experimentation time is something that I ask focus on in my class to teach students about responsibility and time management. It can be easily taught by using the model of “Get Ready, Do, Done”, which shows the students the steps they need to reach a goal and the desired amount of time they should be spending to complete a task within their larger goal:

Get Ready: What materials do you need? How much time do you need?

Do: What steps do you need to take to get you there? How long will they take?

Done: When you are done, what will your task look like/feel like?

This an image of the Get Ready, Do, Done model that I created for my Science class.

Finally, another important ground rule is that students should be comfortable asking partners and classmates for help instead of only relying on the teacher for assistance using the Ask Three Before Me strategy. This allows students to recognize their own personal value in a team setting and enhances the sense of collaboration during assignments, whether it is independent or group work. Knowing that someone else might have solutions to the problems that we run into as we work toward our goal supports the idea that it is good to ask for help and brainstorm with others to solve a problem or issue we may come across during the completion of our goals.

Q. How do we learn from each other, reflect on our progress, and share what we have done?

EM: Having students share their ideas prior to experimentation is a great way for students to talk out what they are expecting to happen based on background knowledge and previous mastery experiences they may have had that relate to this new challenge. I have found that it is important to ask your students to share their claims and support them with evidence and reasons to create a deeper understanding for the students. You can consult the “CER Framework” strategy in the BetterLesson Lab to learn more about how to structure the development of a claim with evidence and reasoning.

After experimentation, I believe that it is important to reflect on the overall process. Asking students what they discovered about their hypothesis requires them to think back about their original hypothesis and start to reorganize what it is that they understand about the concept being tested. This can be done with a partner or as a whole class to show students that many others developed a hypothesis that didn’t turn out to be true, but we can learn from all experiences.

And, once students have reflected on their experience, allowing them to ask “what if” questions can be very motivating and challenging. For example, students could ask themselves or their group members the following questions: “What if we had changed a material?” “What if we had more time to complete this lab?” “What if we used a different amount of liquid in our experiment?” All of these questions create a pattern of understanding for the students who are still forming concepts in their mind. By discovering one aspect of a concept, we can then reflect and expound upon what we know, which brings us back to forming another hypothesis based on our background knowledge and previous experiences. Our questions should lead us to answers, which should eventually lead us right back to having more questions that we want to uncover and understand!

CD: Some strategies that I often recommend to teachers to try in order to support their students to learn from each other, reflect on their process and product, and share their learnings with each other are Student Roles: Democratizing Group Work, 360 Group Reflection, and the Carousel Discussion using a Graffiti Board strategy. Each of these strategies provide scaffolds and frameworks for students to learn from and work with group members on an experiment, reflect on their individual and group work, and then share their work with their peers in a constructive way.

Experimentation taps into students’ own curiosity about the world and helps them practice skills that are valuable both in an academic setting as well as outside the classroom. With a teacher’s guidance, students can start establishing a lifetime of good habits enabling them set, reach, and reflect upon their own goals, whatever they may be.